Trial Spotlight: A Closer Look at ECOG-ACRIN’s Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndrome Studies

October 19, 2023

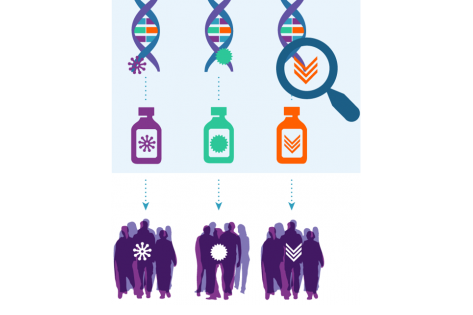

It’s a MATCH: Peter O’Dwyer on the Future of Precision Oncology

October 19, 2023Genetic Testing Challenges and Solutions: A Community and an Academic Perspective

Community Perspective

Community Perspective

By Matthias Weiss, MD

Academic Perspective

Academic Perspective

Kim A. Reiss, MD

Precision Medicine in the Community-Based Clinical Practice (Dr. Weiss)

Community-based hematologist-medical oncologists are facing the significant challenge of learning about and clinically applying the rapidly evolving landscape of molecular- and genomic-driven cancer therapeutics. In an era where medical information doubles every three months, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves between one and four new drugs per month, achieving and maintaining mastery of each new finding and its implications has become nearly impossible. This is especially true for physicians who manage the entire spectrum of benign hematology to malignant hematology and solid tumor medical oncology. Compounding this challenge, most hematologist-medical oncologists have not had dedicated training in molecular oncology, and few community practices have access to precision medicine molecular tumor boards that assist in interpreting genomic results and guiding clinical decision-making in real time.

Additionally, at most practice sites, both at community and academic centers, genomic results are not embedded into the electronic health record (EHR) as discrete data and cannot be searched or used to create mutation- or disease-specific reports.

This troublesome set of complications is most unfortunate at a time when scientific progress has afforded our patients practice-changing genomic-driven interventions. Clinical trial options are abundantly available to evaluate promising new therapeutic interventions.

For example, the ongoing APOLLO trial (EA2192) is evaluating the benefit of adjuvant PARP inhibitor therapy for patients affected by early-stage pancreatic cancer treated with curative intent. Patients with germline or somatic BRCA1/2 and PALB2 mutations are eligible to participate. There is considerable evidence that PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy provides significant benefit for this population in the advanced disease setting, much like that which has been shown in ovarian and breast cancer.

Even more importantly, the results of the OlympiA trial (NCT02032823) of adjuvant olaparib for patients with early-stage, BRCA-related breast cancer led to the FDA approval of olaparib for this indication based on a significant progression-free survival and overall survival benefit. However, the APOLLO trial is not accruing at the anticipated pace. As per National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, genetic counseling and testing are recommended for all patients afflicted by pancreatic cancer, whereas somatic testing is not yet.

From my perspective as a community hematologist-medical oncologist, there are several strategies to approach the above-listed challenges:

- Establish a precision medicine program with dedicated staff and physician leadership to: establish the logistics of next-generation sequencing (NGS) test ordering and result reporting; coordinate complex related care; collaborate with experts in molecular oncology within and outside of the local institution; provide interpretation, clinical management, and trial matching support to your care team colleagues; and disseminate practice-changing related medical information

- Identify and select NGS providers that report genomic results as discrete data in your EHR, notify you and your team of the best standard-of-care options for your specific patient, identify clinical trial options, and enable the creation of genomic data practice performance metrics reports

- Identify opportunities for support by academic centers or virtual molecular tumor boards to be a ready and established resource to facilitate patient care assistance in real time

- Consider a “just-in-time” clinical trial portfolio, encompassing both National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) and industry-sponsored trials, that can be accessed for the right patient presentation and genomic alteration within a few weeks

- Consider a “sub-specialization” strategy among your community-based hematologist-medical oncologists to function as disease-specific resources for your team

I invite attendees of the upcoming ECOG-ACRIN Fall 2023 Group Meeting to participate in the Community Cancer Committee Session at 3:00 PM on October 26, when we will review these options in more detail.

Precision Medicine in the Academic Cancer Center (Dr. Reiss)

The NCCN guidelines recommend germline genetic testing for all patients diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer, regardless of stage. This recommendation is based on studies showing a prevalence of pathogenic or likely pathogenic (PV/LPV) germline variants in up to 17% of tested patients.1, 2, 3, 4 PVs/LPVs may have urgent treatment implications and have obvious connotations for a patient’s family. Thus, we are obligated to offer prompt germline testing to our patients whenever possible. However, there are significant challenges associated with getting timely genetic testing for this high-acuity population, the most prominent of which is identifying genetic counseling appointments. Genetic counselors are scarce, and time to appointments can range from weeks to months. Additionally, patients are ill and already overburdened with medical appointments and (often) hospitalizations.

As a result of several years of work and a prior research collaboration with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC),5 we at the Abramson Cancer Center now use point-of-care testing, also known as mainstreaming, for our pancreatic cancer patients. In this model, patients are prompted to access an educational video in their electronic medical record prior to their first medical oncology appointment and are consented for testing by the medical oncologist during the visit. Consent includes a brief discussion regarding possible implications of a PV/LPV or of a variant of uncertain significance. An informational brochure is also provided, and consent is documented in the chart. Patients who agree to be tested typically have their blood drawn before leaving the clinic. All results are disclosed via the genetic counselor.

We have found that using this model, >90% of our pancreatic cancer patients receive germline genetic testing on the day of their first medical oncology appointment. The method has been found to be acceptable to patients and providers and has improved front-line therapy selection and clinical trial enrollment to genetically-targeted studies. We recognize that the consent process is truncated compared to standard practice but feel that for a population of pancreatic cancer patients, obtaining the testing is paramount. Additionally, some of the issues surrounding genetic testing concerns (such as long-term risks of a genomic finding) are typically less critical for our population.

Obtaining genetic testing for patients with pancreatic cancer is a highly challenging undertaking, particularly given limited resources. Creating a process by which medical oncologists consent and test patients in the clinic, with genetic counseling assistance as needed, is acceptable to patients and results in much-improved testing rates.

Dr. Weiss is a hematologist-oncologist at ThedaCare Regional Cancer Center in Appleton, Wisconsin, where he is the medical director for the Research and Precision Medicine Program. He chairs the ECOG-ACRIN Community Cancer Committee and is a member of ECOG-ACRIN’s Executive Committee and Principal Investigator Committee.

Dr. Reiss is an associate professor of medicine and medical oncologist at the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where she is also co-leader of the Cancer Therapeutics Program. She co-chairs the ECOG-ACRIN Gastrointestinal Cancer Committee and is the study chair for the EA2192/APOLLO trial.

1Goggins M, Schutte M, Lu J, et al. Germline BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with apparently sporadic pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res 1996; 56(23): 5360-4.

2Couch FJ, Johnson MR, Rabe KG, et al. The prevalence of BRCA2 mutations in familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16(2): 342-6.

3Salo-Mullen EE, O'Reilly EM, Kelsen DP, et al. Identification of germline genetic mutations in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2015; 121(24): 4382-8.

4Stadler ZK, Salo-Mullen E, Patil SM, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish families with breast and pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2012; 118(2): 493-9.

5Hamilton JG, Symecko H, Spielman K, et al. Uptake and acceptability of a mainstreaming model of hereditary cancer multigene panel testing among patients with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. Genet Med 2021; 23(11): 2105-13.

![ECOG-ACRIN logo[19516]275×75](https://blog-ecog-acrin.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ECOG-ACRIN-logo19516275x75.png)